Do we know where we’re going? And how confident are we that we’ll get there?

Indulge me in a little geekiness:

I was reading an article in Nautilus the other day (if you’re not familiar with Nautilus, you should check it out; it’s an online and print magazine of diverse, brilliant articles for curious people) and came across a word that I wasn’t familiar with: ephemerides.

Thought Cloud

Ephemerides is the plural of ephemeris, which looks like, and shares the same “thought cloud” as, ephemeral. A thought cloud is an imaginary swirl of all the words you might encounter in pondering a given subject. In this case, the subject would be something like “Things That Are Fleeting, Imprecise, or Illusory.” Merriam-Webster defines ephemeris as “a tabular statement of the assigned places of a celestial body for regular intervals.”

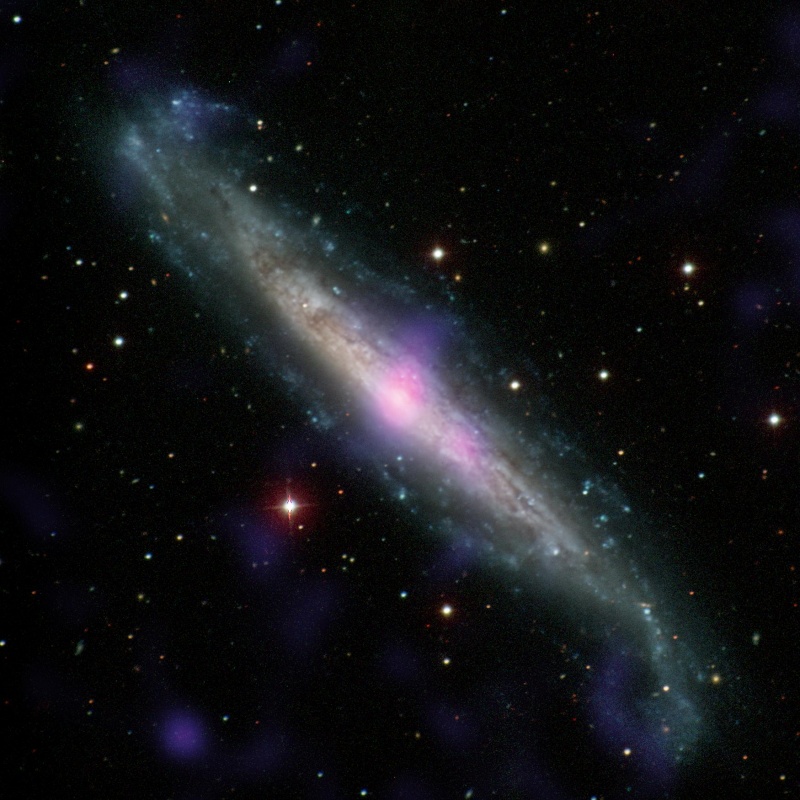

The crux of the matter is that you never know precisely where an object in outer space is. Astro-physicists and other space scientists use enormously complicated (at least to me) mathematics to calculate their best well-educated guesses of where any given object will be at any given time. When those calculations are gathered into a table for a particular object, the result is called an ephemeris. A bunch of those are called ephemerides.

You can see why ephemeris shares a thought cloud with ephemeral. The position of a planet, star, or other celestial body is never static. Any calculated location is fleeting, transitory—the very antithesis of permanent. In other words, ephemeral.

Position Errors

The further away the goal, the greater the potential error in calculation. For instance, when the New Horizons probe set out in 2006 for the former planet Pluto, a trip anticipated to cover some 5 billion kilometers, the goal’s location was calculated to within 0.00014 degrees of angle. That sounds pretty precise to me.

Over that distance, however, this seemingly infinitesimal wiggle in the angle of location translates into 13,000 kilometers of potential position error.

Whoa, right?

Well, check this: the folks at NASA and Jet Propulsion Labs and wherever else they do such things are contemplating a mission to the Alpha Centauri star system—four light-years away—via “nanocraft” scooting along at 20% the speed of light (134 million miles per hour), powered by light sails filled by laser beams (I know, sounds like science fiction, but I swear I’m not joking) in a mission that will take twenty years.

Proxima Centauri, the nearest star in the target system, moves relative to Earth at, give or take, 32.19 kilometers per second. But if you give or take a minuscule 0.01 kilometers per second, over the length of the mission, you’re looking at a positional error of more than 6 million kilometers.